Pensions have never been especially exciting. Usually, it takes a crisis, like a company collapsing and retirees being deprived of their dues, for a pension fund to make the news. But as the world’s largest pool of assets they matter enormously. And since they’re often a company’s biggest liability, their funded status is also hugely important.

The funded status of a defined benefit pension fund is the present value of net cash flows. It depends on the composition of assets, their growth rate, and, most importantly, the discount rate of liabilities.

Throughout the 1990s pension funds held around 70% in equities and 30% in fixed income. They enjoyed a substantial surplus in their funded status. Roll on to the next decade, though, and things began to change. Since the early 2000s, when interest rates fell sharply, the funded status became a constant struggle: even if assets performed strongly, low rates would prevent the fund’s recovery. When rates are on the rising cycle, funded ratios become healthier. Meanwhile, Liability Driven Investment (LDI) policies prompted pension funds to shift their allocation towards fixed income.

PENSION PUSHMI-PULLYU

Last year is a case in point. Discount rates declined to new lows while asset returns exceeded expectations. And while these two factors pulled the funded ratio in opposite directions, increases in liabilities overwhelmed asset growth: the funded status of major corporate pension plans declined by an average 1.5%.

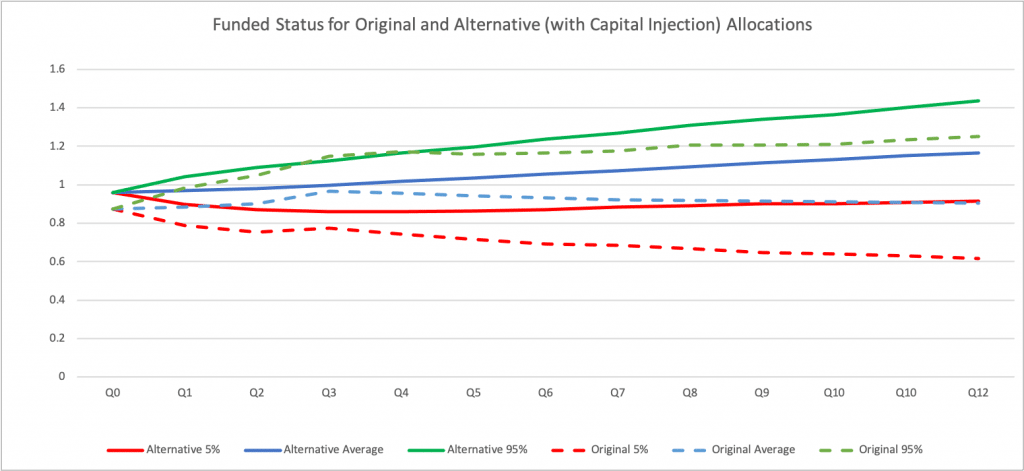

While pension plans target full funding, they are considered at risk of defaulting on their liabilities if their funded ratios expect to dip below 80% percent, or under 70% under ‘worst-case’ scenarios.

A simple sensitivity analysis of funded ratios to interest rate movements isn’t sufficient, due to the dynamic correlations of rates, credits spreads, equity markets, and other risk factors impacting assets and liabilities. You can’t check rate moves in isolation, without considering all other factors, especially given the long-term nature of pension liabilities.

So if a funded ratio is slightly above 80%, how can we estimate its chances of plunging into insolvency, and what can be done to prevent this from happening?

Even underfunded pension funds can – most of the time – pay liability cash flows (people’s pensions) for a while. The problem with such funding is that these ongoing payments eat into the asset base, reducing its growth prospects and the chances of improving the funded ratio.

THE BUNDLE SOLUTION

To stop this vicious circle, a pension fund can revise its strategic allocation, overlay hedging strategies, or close the gap with a capital injection, as, for example, BAE Systems did last year, with an extra £1bn.

If you consider a distribution cone of the funded ratio, capital infusion would provide an upward shift, optimal asset allocation would tilt it up, and a wise hedging strategy makes it narrower. Given that pension risk is asymmetric (i.e. the downside risk tremendously overwhelms the upside benefit), the more you can avoid deterioration of funded status, the better.

In the current market environment, the combination of all three strategies might be highly effective. You just need to identify the minimal amount of capital required to prevent the long-term erosion of the asset base during turbulent markets, and support the recovery of the funded ratio afterwards.

To combine this with optimal asset allocation and hedging strategies in a perfect bundle, one needs long-term scenarios with realistic dynamics of underlying market factors. Such scenarios incorporate all market dynamics and allow us to realistically project funded ratio perspectives. Any other risk/return estimation methods that use static correlations, short-term Value-at-Risk or single factor sensitivity analysis might lead you to a pension obligation bond trap.

This bundle solution may not sound especially sexy, but it could be the difference between unwanted headlines, and remaining happily out of the spotlight.